Let's face it, 2014 was full of lamentable news events, and while I'm usually able to maintain an optimistic outlook by looking at the big picture, I'm also resigned to the media rarely sharing that viewpoint. So I was completely surprised to see a wave of overall "good news" articles popping up in the last week. I've followed (and written) articles like this for years, and I can't remember the last time I saw this many written at the same time.

Some of it is inspired by economic news. By all accounts, the economy has been successfully recovering for a while now, although not necessarily in a way - or at a pace - that benefits everyone. But here's a New York Times article about the economic recovery finally spreading to the middle class in the form of wage gains.

I don't usually talk about specific economic news when discussing the Secret Peace, because I'm more concerned with long-term trends than with any specific economic cycle. The economy goes up, and the economy goes down, once a decade or so, and it always will. That's why I was glad to see other positive articles focusing on issues beyond rising consumer confidence and falling gas prices.

Michael Grunwald's article in Politico, for example, talks a lot about the economy but also raises good points about the press's negative focus and our reluctance to discuss good news. He writes, "This bah-humbug brand of moral superiority has flourished since the crisis: How dare you celebrate this or that piece of economic data when so many Americans are still hurting? It’s awkward to argue with that view, since many Americans are indeed still hurting. But the economic data keep showing that fewer Americans are hurting every month. ... Better is better than worse."

He goes on to write, "Let’s face it: The press has a problem reporting good news. Two Americans died of Ebola and cable TV flipped out; now we're Ebola-free and no one seems to care. The same thing happened with the flood of migrant children across the Mexican border, which was a horrific crisis until it suddenly wasn't. Nobody’s going to win a Pulitzer Prize for recognizing that we're smoking less, driving less, wasting less electricity and committing less crime. Police are killing fewer civilians, and fewer police are getting killed, but understandably, after the tragedies in Ferguson and Brooklyn, nobody's thinking about that these days. The media keep us in a perpetual state of panic about spectacular threats to our safety — Ebola, sharks, terrorism — but we’re much likelier to die in a car accident. Although, it ought to be said, much less likely than we used to be; highway fatalities are down 25 percent in a decade."

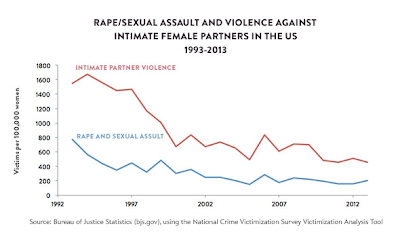

For an even more comprehensive look at the big picture, Steven Pinker can always be relied upon for well-researched, compelling updates. In this Slate article, he and Andrew Mack try to get past the sensationalism of the media and examine trends objectively, by tallying numbers. Take a look at some of these excellent charts:

They write, "The world is not falling apart. The kinds of violence to which most people are vulnerable—homicide, rape, battering, child abuse—have been in steady decline in most of the world. Autocracy is giving way to democracy. Wars between states—by far the most destructive of all conflicts—are all but obsolete. ... We have been told of impending doom before: a Soviet invasion of Western Europe, a line of dominoes in Southeast Asia, revanchism in a reunified Germany, a rising sun in Japan, cities overrun by teenage superpredators, a coming anarchy that would fracture the major nation-states, and weekly 9/11-scale attacks that would pose an existential threat to civilization. Why is the world always “more dangerous than it has ever been” — even as a greater and greater majority of humanity lives in peace and dies of old age?"

Topping even Pinker and Mack's charts is this Vox.com article listing 26 important charts that show the world is getting better. Their charts cover wildly different stats - much like my book - that all add up to an improving world. Some highlights:

Lastly, astronaut Chris Hadfield leaves us with this short uplifting look at the state of the world - and an excellent challenge for each of us to make the most of 2015. Happy new year!